Ahmad Fauzi Abdul Hamid | 12nd November 2021

For political philosophers, the term ‘social contract’ will be familiar as the title of a book published in 1762 by Jean Jacques Rousseau. Whether effected in the real or hypothetical realm, as an oral or written undertaking, the existence of a social contract protects commoners from overlordship of people in power, be they hereditary rulers or elected politicians. Basically, in exchange for political authority, which entails the power to make laws and regulations in order to organise society, leaders in positions of authority are burdened with tasks and responsibilities to protect and defend rights of the people deemed as inalienable by virtue of their being human beings. Governments are considered to be fulfilling a social contract whenever they further interests of members of a polity, as obtained in John Locke’s maxim of ‘life, liberty and property,’ the USA’s Declaration of Independence’s ‘‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,’ or, in the eyes of Muslim maqasid sharia (higher objectives of Islamic law) theoreticians, the five fundamental objectives of faith (Arabic: din), life (Arabic: nafs), intellect (Arabic: aql), family (Arabic: nasl), and wealth (Arabic: mal).

For political philosophers, the term ‘social contract’ will be familiar as the title of a book published in 1762 by Jean Jacques Rousseau. Whether effected in the real or hypothetical realm, as an oral or written undertaking, the existence of a social contract protects commoners from overlordship of people in power, be they hereditary rulers or elected politicians. Basically, in exchange for political authority, which entails the power to make laws and regulations in order to organise society, leaders in positions of authority are burdened with tasks and responsibilities to protect and defend rights of the people deemed as inalienable by virtue of their being human beings. Governments are considered to be fulfilling a social contract whenever they further interests of members of a polity, as obtained in John Locke’s maxim of ‘life, liberty and property,’ the USA’s Declaration of Independence’s ‘‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,’ or, in the eyes of Muslim maqasid sharia (higher objectives of Islamic law) theoreticians, the five fundamental objectives of faith (Arabic: din), life (Arabic: nafs), intellect (Arabic: aql), family (Arabic: nasl), and wealth (Arabic: mal).

In Malaysia, we could conceive of such a social contract having taken place during the formation of Malaysia on 16 September 1963, when Sabah and Sarawak agreed to join the Federation on a 20-point agreement and 18-point agreement respectively. Some points of the agreements were incorporated into the Federal Constitution, but some were not. Due to their lack of legal bases in official documents, some of these powers are seen to have been eroded throughout the years, leading to recent calls for the restoration of both Sabah and Sarawak’s regional sovereignty to be on par with Peninsular Malaysia (previously ‘Malaya’) as a whole rather than as just two of Malaysia’s thirteen states. How do social contract clauses function in practice? On immigration matters, for example, Peninsular Malaysians would surely be aware of the requirements to produce one’s passport or identity card at the point of entry into both states, despite being citizens of the same country. Opposition politicians from the Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition have on several occasions been denied entry on the orders of the Sarawak state government. This inconvenience has become a way of life for local visitors to Sabah and Sarawak. Can we imagine the reaction of Sabahans and Sarawakians if it were to be announced that terms of the Malaysia Agreement 1963 ‘advantageous’ to them are to be revoked?

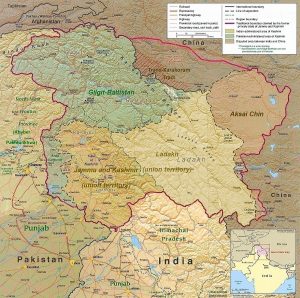

Having understood the philosophy behind the notion of a social contract, we are in a better position to empathise with the plight of the Kashmiris since 5 October 2019, when Articles 370 and 35(a) were abolished by presidential decree and approved by India’s Parliament, which is dominated by the staunchly Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has ruled India since 2014 and had just emerged from a fresh renewal of its national mandate in the May 2019 polls. Both provisions had recognised Kashmir’s special status within India – part of a modus vivendi consented to by the Muslim leaders of Jammu and Kashmir and secular-nationalist leaders of India as integral terms governing the region’s accession to India instead of Pakistan at the height of communal troubles following the India-Pakistan partition of 1947.

For the record, Jammu and Kashmir, which existed as India’s only Muslim-majority state from 1954 until 2019, had consisted of three administrative regions, viz. Muslim-majority Kashmir valley, Hindu-majority Jammu and Buddhist-majority Ladakh on the province’s east. The 2019 Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act reduced the state to the two union territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh. Their peoples were stripped off all privileges associated with the now abrogated Articles 370 and 35(a), which entailed, among other things, powers to institute laws separate from India’s jurisdiction except in financial, defence, foreign policy and communications affairs; to hoist a separate flag on official occasions; and to regulate property ownership, residency and citizenship requirements which had barred outsiders from exploiting Jammu and Kashmir’s resources (Al Jazeera 2019).

For the record, Jammu and Kashmir, which existed as India’s only Muslim-majority state from 1954 until 2019, had consisted of three administrative regions, viz. Muslim-majority Kashmir valley, Hindu-majority Jammu and Buddhist-majority Ladakh on the province’s east. The 2019 Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act reduced the state to the two union territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh. Their peoples were stripped off all privileges associated with the now abrogated Articles 370 and 35(a), which entailed, among other things, powers to institute laws separate from India’s jurisdiction except in financial, defence, foreign policy and communications affairs; to hoist a separate flag on official occasions; and to regulate property ownership, residency and citizenship requirements which had barred outsiders from exploiting Jammu and Kashmir’s resources (Al Jazeera 2019).

The twin nullification of Articles 370 and 35(a), which had been operative since 1949 and 1954 respectively, meant that Indians from other states could now settle permanently and acquire property in Jammu and Kashmir (Farooq and Javaid 2020). Reports immediately surfaced of the central government planning to create permanent Hindu settlements in the newly created territory modelled on the Israeli ‘settler colonialism’ policy in the occupied Palestinian territories (Lateef 2021). Such a resettlement programme involved bringing back an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 local Hindus known as Pandits who had fled Kashmir since 1989 when the state erupted in troubles pitting Kashmiri separatists against the Indian army (Ghoshal and Pal 2019). Chief minister of Haryana state bordering Delhi, Manohar Lal Khattar, even insultingly joked: “Our Dhakarji used to say we will bring in girls from Bihar. Now they say Kashmir is open, we can bring girls from there” (quoted in Roy 2019).

While we often hear about inconveniences suffered due to successive Covid-19 lockdowns imposed that severely restrict our movements during the pandemic, Kashmiris endured such conditions for almost two years from August 2019 to February 2021, when 4G internet services were restored. A security-cum-communication lockdown was nonetheless re-imposed in early September 2021 on the occasion of the death of veteran Kashmiri freedom fighter Syed Ali Shah Geelani. Geelani’s 92-year old body was tragically snatched by the Indian military in the wee hours of 2 September and given a lone burial in a clear attempt to prevent unrest in the event of a public funeral (Ahmad 2021). Geelani had been an uncompromising figure in demanding a plebiscite for Kashmiris; a demand that was in accordance with United Nations (UN) Security Council Resolution No. 47 adopted on 21 April 1948 but never honoured by India.

For all of India’s claims to secularism as a foundational principle of its nation state (Kalim, Soherwordi and Syed 2020), Kashmir’s right to self-determine its future: whether to be part of India or Pakistan or an independent nation state of its own, was never respected. Holding Kashmiris incommunicado was important to the BJP government’s strategy of isolating Kashmiri Muslims from the ummah (global Muslim community). BJP is especially wary of subversive elements entering India from Pakistan whom it accuses of supplying ammunition and manpower to foment rebellious activities in the Muslim-dominated areas of Jammu and Kashmir (Al Jazeera English 2018). It would not be in India’s geo-strategic interests to launch a full-scale military confrontation against Pakistan; both nuclear powers had already been to war thrice, in 1965, 1971 and 1999. Some geo-strategists have gloomily predicted that troubles in Kashmir could very well be a catalyst for a future world war (Rais 2019). Unfortunately, India’s dismal human rights record throughout its occupation of Kashmir is prodding desperate young Muslims into the clutches of extremist organisations such as Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) and the Indian chapter of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). According to these movements’ Salafi-jihadist apocalyptic worldview, no room exists at all for co-existence with between India’s Muslims and non-Muslims, who have proven themselves to be sworn enemies of Islam, as exemplified most powerfully in the destruction of the Babri Mosque in Ayodha, Uttar Pradesh, in 1992 (Prasad 2019).

For all of India’s claims to secularism as a foundational principle of its nation state (Kalim, Soherwordi and Syed 2020), Kashmir’s right to self-determine its future: whether to be part of India or Pakistan or an independent nation state of its own, was never respected. Holding Kashmiris incommunicado was important to the BJP government’s strategy of isolating Kashmiri Muslims from the ummah (global Muslim community). BJP is especially wary of subversive elements entering India from Pakistan whom it accuses of supplying ammunition and manpower to foment rebellious activities in the Muslim-dominated areas of Jammu and Kashmir (Al Jazeera English 2018). It would not be in India’s geo-strategic interests to launch a full-scale military confrontation against Pakistan; both nuclear powers had already been to war thrice, in 1965, 1971 and 1999. Some geo-strategists have gloomily predicted that troubles in Kashmir could very well be a catalyst for a future world war (Rais 2019). Unfortunately, India’s dismal human rights record throughout its occupation of Kashmir is prodding desperate young Muslims into the clutches of extremist organisations such as Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) and the Indian chapter of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). According to these movements’ Salafi-jihadist apocalyptic worldview, no room exists at all for co-existence with between India’s Muslims and non-Muslims, who have proven themselves to be sworn enemies of Islam, as exemplified most powerfully in the destruction of the Babri Mosque in Ayodha, Uttar Pradesh, in 1992 (Prasad 2019).

To be fair, India’s brand of secularism was of a moderate variety: one which ostensibly accommodated religious diversity and multi-culturalism in line with India’s cosmopolitan character (Mahajan 2017). This was especially true, and only true, during the Congress Party’s rule in India, and even then, limited to only Jawaharlal Nehru’s years in power (1947-1964). The importance of Kashmir to Nehru’s scheme of a secular governance is elaborated by Behera (2002: 346) as follows:

Kashmir was central to Nehru’s objective of establishing the secular basis of the Indian state. Its inclusion was necessary not only for fighting an older and larger battle of secular nationalism vis-a-vis Pakistan’s two-nation theory, but also for confronting its old ideological adversary at home—that is, Hindu nationalism …. Accordingly, Nehru was prepared to go the extra mile in accommodating the political aspirations of Kashmiris and assured them that the state’s future was secure in a federal, democratic and secular India. Kashmir was granted special status under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution. No provision of the Constitution except Article 1 (bringing it under the territorial jurisdiction of India) was made applicable to the state.

Within just one generation, dangers of secular India’s social contract with Jammu and Kashmir unravelling was evident as the Congress Party under Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi, who was Prime Minister in 1966-1977 and 1980-1984, increasingly pandered to the demands of Hindu nationalists whose vision of India as a nation state was built upon the political doctrine of Hindutva or ‘Hinduness,’ with the creation of a Hindu rashtra (nation) being its ultimate goal. Within such a worldview, non-Hindus were constructed as ‘Others,’ whose belonging to India depended on the extent to which they willingly submitted to Hindu nationalist beliefs and principles. Among these non-Hindu ‘Others,’ there was further differentiation between adherents of splinter religions from Hinduism, viz. Jainism, Sikhism and Buddhism, and Muslims and Christians whose devotion to alien faiths may pose an existential threat to a ‘New India’ run on Hindutva precepts (Bajpai 2017). Through the penetration of state institutions by Hindutva proponents in far-right voluntary organisations such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), Muslims have been demonised in the contemporary Indian national imagination as ‘terrorists,’ ‘child abductors,’ ‘seducers of Hindu girls’ and ‘Corona jihad’ vectors intent on infecting the Hindu population with Coronavirus. This has led to a spate of lynchings of Muslims across the country but which became especially acute in the cow-belt states of northern India (Sikander 2021).

Within just one generation, dangers of secular India’s social contract with Jammu and Kashmir unravelling was evident as the Congress Party under Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi, who was Prime Minister in 1966-1977 and 1980-1984, increasingly pandered to the demands of Hindu nationalists whose vision of India as a nation state was built upon the political doctrine of Hindutva or ‘Hinduness,’ with the creation of a Hindu rashtra (nation) being its ultimate goal. Within such a worldview, non-Hindus were constructed as ‘Others,’ whose belonging to India depended on the extent to which they willingly submitted to Hindu nationalist beliefs and principles. Among these non-Hindu ‘Others,’ there was further differentiation between adherents of splinter religions from Hinduism, viz. Jainism, Sikhism and Buddhism, and Muslims and Christians whose devotion to alien faiths may pose an existential threat to a ‘New India’ run on Hindutva precepts (Bajpai 2017). Through the penetration of state institutions by Hindutva proponents in far-right voluntary organisations such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), Muslims have been demonised in the contemporary Indian national imagination as ‘terrorists,’ ‘child abductors,’ ‘seducers of Hindu girls’ and ‘Corona jihad’ vectors intent on infecting the Hindu population with Coronavirus. This has led to a spate of lynchings of Muslims across the country but which became especially acute in the cow-belt states of northern India (Sikander 2021).

The significance of Kashmir in all this new political equation lies in the images of Articles 370 and 35(a) as symbols of Muslim resistance against integration with the dominant Hindu polity – an adamance that was unfortunately sanctioned by the state. As Chandra (2020) perceptively observes, “Kashmiri Muslims as colonial subjects stand metonymically for all Indian Muslims.” The more than half a century old social contract simply had to be jettisoned if the Hindutva vision, as propagated by the likes of RSS, its political offspring the BJP and its loyalist Narendra Modi, Prime Minister since 2014 whose abysmal human rights record against Muslims is showcased by his complicity as then Chief Minister during the Gujarati anti-Muslim pogroms of 2002, is to be realised (Komireddi 2019). Yet, the tragedy of India’s betrayal of its Muslim citizens is compounded by the fact that it was early Kashmiri Muslim nationalists such as Sheikh Abdullah aka Sher-e-Kashmir (1905-1982) who had preferred accession of Kashmir to India instead of Pakistan. While spurning the idea of Pakistan for its religious pretensions, the attraction of India for Sheikh Abdullah lay precisely in its secularism and the pluralist concern for minorities that such a polity seemed to imply would be accommodated (Kak 2020). The apparent readiness of Congress leaders to concede Articles 370 and 35(a) was just the assurance needed to calm down Muslim fears of future discrimination. This was despite indications from all directions that even the arch-secularist Nehru had conceived of such concessions as merely a tactical strategy, or in other words, a temporary provision at best (Behera 2020).

On the religious front, if Hindu devotees think that embracing the Hindutva ideology would bring them closer to Hinduism, they might be in for a rude shock to discover that Hindutva’s origins are properly located not in some ancient Hindu rites or philosophy, but rather in the unholy marriage between a Hinduised political framework and European national socialism in the mould of inter-war German Nazism and Italian fascism. As convincingly exposed by Leidig (2020), the trans-continental links were not restricted to the intellectual realm; they in fact involved funding, institutional and personnel support, and marriages. Even the RSS, out of whose womb was born BJP and racist cadres like Narendra Modi, was inspired by Mussolini’s Voluntary Militia for National Security, otherwise known as the Blackshirts (Roy 2019). As explained at length by the eminent Indian historian, Romila Thapar, Hindutva is never nearly the same as Hinduism (Johnjitheesh 2021). Hindutva, which she calls ‘Syndicated Hinduism,’ stresses a rediscovery of the Hindu identity via political claims, whereby nationalist assertions approach a sacred status. As a female Kashmiri Hindu author notes as far back as five years ago, “The Kashmiri Pandit issue is used by Hindutva ideologues to bash and demonise (Kashmiri) Muslims” (Kaul 2016).

On the religious front, if Hindu devotees think that embracing the Hindutva ideology would bring them closer to Hinduism, they might be in for a rude shock to discover that Hindutva’s origins are properly located not in some ancient Hindu rites or philosophy, but rather in the unholy marriage between a Hinduised political framework and European national socialism in the mould of inter-war German Nazism and Italian fascism. As convincingly exposed by Leidig (2020), the trans-continental links were not restricted to the intellectual realm; they in fact involved funding, institutional and personnel support, and marriages. Even the RSS, out of whose womb was born BJP and racist cadres like Narendra Modi, was inspired by Mussolini’s Voluntary Militia for National Security, otherwise known as the Blackshirts (Roy 2019). As explained at length by the eminent Indian historian, Romila Thapar, Hindutva is never nearly the same as Hinduism (Johnjitheesh 2021). Hindutva, which she calls ‘Syndicated Hinduism,’ stresses a rediscovery of the Hindu identity via political claims, whereby nationalist assertions approach a sacred status. As a female Kashmiri Hindu author notes as far back as five years ago, “The Kashmiri Pandit issue is used by Hindutva ideologues to bash and demonise (Kashmiri) Muslims” (Kaul 2016).

In a nutshell, to Hindu nationalists, religious identity ought to be manipulated for the furtherance of partisan political objectives. For want of a better comparison, the Hindutva ideology has corrupted the spiritual essence of Hinduism in more or less the same manner that Islamism has defiled Islam and Zionism has secularised Judaism.

References:

Ahmad, Zia. (2021). Kashmir under military lockdown after freedom fighter dies. Australasian Muslim Times, 3 September. Retrieved from: https://www.amust.com.au/2021/09/kashmir-under-military-lockdown-after-freedom-fighter-dies/

Al Jazeera English. (2018). The Kashmir conflict, explained. Al Jazeera, 27 June. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CDpEmvjx12I

Al Jazeera. (2019). Kashmir special status explained: What are Articles 370 and 35(a)?. Al Jazeera, 27 June. Retrieved from: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/8/5/kashmir-special-status-explained-what-are-articles-370-and-35a

Bajpai, Rochana (2017), ‘Secularism and Multiculturalism in India: Some Reflections’, in Anna Triandafyllidou and Tariq Modood (eds.), The Problem of Religious Diversity: European Challenges, Asian Approaches, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 204-227.

Behera, Navnita Chadha. (2002). Kashmir: A testing ground, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 25(3), 343-364. DOI: 10.1080/00856400208723506.

Chandra, Uday. (2020). The making of a Hindu India. Al Jazeera, 24 August. Retrieved from: https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2020/8/24/the-making-of-a-hindu-india

Farooq, Muhammad, and Javaid, Umbreen. (2020). Suspension of Article 370: Assessment of Modi’s Kashmir Masterstroke under Hindutva Ideology. Global Political Review, V(1), 1-8. DOI: 10.31703/gpr.2020(V-I).01

Ghoshal, Devjot, and Pal, Alasdair. (2019). Exclusive: BJP to revive plan for Hindu settlements in Kashmir. Reuters, 12 July. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/india-kashmir-hindu-ram-madhav-idINKCN1U712X

Johnjitheesh, Jipson P.M. (2021). Interview: Romila Thapar ‘Hindutva is not the same as Hinduism’. Frontline, 7 May. Retrieved from: https://frontline.thehindu.com/the-nation/interview-romila-thapar-historian-hindutva-not-the-same-as-hinduism/article34360442.ece

Kak, Shakti. (2009). Hindutva, the Crisis of the State and Political Mobilisation in Jammu and Kashmir. Contemporary Perspectives, 3(1), 14-33. DOI: 10.1177/223080750900300102

Kaul, Nitasha. (2016). Kashmiri Pandits Are a Pawn in the Games of Hindutva Forces. The Wire, 7 January. Retrieved from: https://thewire.in/communalism/kashmiri-pandits-are-a-pawn-in-the-games-of-hindutva-forces

Kalim, Inayat; Soherwordi, Syed Hussain Shaheed and Syed, Areeja. (2020). Hindutva in India: Rise of Bigotry against Muslims. South Asian Studies: A Research Journal of South Asian Studies, 35(2), 327-340.

Komireddi, Kapil. (2019). The Kashmir isn’t about territory. It’s about a Hindu victory over Islam. Washington Post, 16 August. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/the-kashmir-crisis-isnt-about-territory-its-about-a-hindu-victory-over-islam/2019/08/16/ab84ffe2-bf79-11e9-a5c6-1e74f7ec4a93_story.html

Lateef, Samaan. (2021). India’s Intifada: Why Modi Is Arresting pro-Palestinian Protesters. Haaretz, 23 May. Retrieved from: https://www.haaretz.com/world-news/india-s-intifada-why-modi-is-arresting-pro-palestinian-protesters-in-kashmir-1.9826301

Leidig, Eviane. (2020). Hindutva as a variant of right-wing extremism. Patterns of Prejudice, 54(3), 215-237. DOI: 10.1080/0031322X.2020.1759861

Mahajan, Gurpreet. (2017), ‘Living with Religious Diversity: The Limits of the Secular Paradigm’, in Anna Triandafyllidou and Tariq Modood (eds.), The Problem of Religious Diversity: European Challenges, Asian Approaches, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 75-92.

Prasad, Hari. (2019). The Salafi-Jihadist Reaction to Hindu Nationalism. Current Trends in Islamist Ideologies, 11 July. Retrieved from: https://www.hudson.org/research/15137-the-salafi-jihadist-reaction-to-hindu-nationalism

Rais Hussin. (2019). Kashmir may be the powderkeg that sparks WW IV. The Star Online, 9 August. Retrieved from: https://www.thestar.com.my/opinion/letters/2019/08/09/kashmir-may-be-the-powderkeg-that-sparks-ww-iv

Roy, Arundhati. (2019). The Silence is The Loudest Sound. New York Times, 15 August. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/15/opinion/sunday/kashmir-siege-modi.html

Ahmad Fauzi Abdul Hamid is Professor of Political Science, School of Distance Education, and Consultant Researcher with the Centre for Policy Research and International Studies (CenPRIS), Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Penang, Malaysia. This essay was first published as a chapter in the book Deadly Silence: Kashmir Facing a Slow Death. And republished by AsiaWe Review at https://www.asiawereview.com/politics/the-jammu-and-kashmir-tragedy-failure-of-indian-secularism/

Ahmad Fauzi Abdul Hamid is Professor of Political Science, School of Distance Education, and Consultant Researcher with the Centre for Policy Research and International Studies (CenPRIS), Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Penang, Malaysia. This essay was first published as a chapter in the book Deadly Silence: Kashmir Facing a Slow Death. And republished by AsiaWe Review at https://www.asiawereview.com/politics/the-jammu-and-kashmir-tragedy-failure-of-indian-secularism/