Emir Hadzikadunic || 3 April 2023

In February 2008, late Saudi King Abdullah delivered a strong warning indicating that Riyadh would suspend its relations with Tehran. A leaked cable from the US Embassy asserted that Abdullah also urged a US delegation to put an end to the Iranian nuclear program. The cable quoted the king as saying, “Cut off the head of the [Iranian] snake”. Since then, two rival states have engaged in a contest for regional supremacy or, at minimum, in a competition to maintain their relative positions in new battlegrounds from Iraq, Bahrain, Syria, Lebanon to Yemen.

In February 2008, late Saudi King Abdullah delivered a strong warning indicating that Riyadh would suspend its relations with Tehran. A leaked cable from the US Embassy asserted that Abdullah also urged a US delegation to put an end to the Iranian nuclear program. The cable quoted the king as saying, “Cut off the head of the [Iranian] snake”. Since then, two rival states have engaged in a contest for regional supremacy or, at minimum, in a competition to maintain their relative positions in new battlegrounds from Iraq, Bahrain, Syria, Lebanon to Yemen.

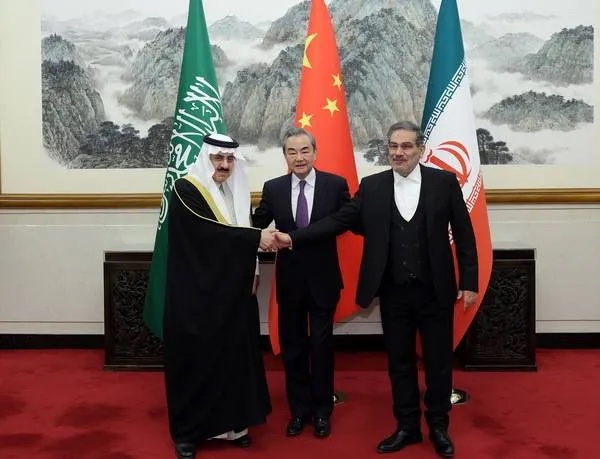

Riyadh seemed to look for opportunities to pass the buck: get its more powerful ally to do the heavy lifting in order to contain the threat from Tehran. But the US did not “cut off the head of the [Iranian] snake” and Saudis were largely alone in their unfriendly business with Iran. Until they decided otherwise in March 2023. The subject of recent Saudi-Iranian détente as well as the likely prospects for their bilateral ties has attracted increasing attention lately. However, most policy experts rarely analyze their earlier rapprochements, why each friendly period in nearly 100 years of their diplomatic history lasted for so long, and when and why things changed. This article addresses this lacuna.

History that projects their trajectory

The in-depth historical account of diplomatic relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia since the 1920s points to a systemic recurrence of friendlier behavior. In my earlier writings on the subject, three separate and relatively friendly periods were identified, the first of which evolved in the multipolar world in late 1920s and early 1930s, the second in the bipolar world from 1946 to 1979, and a third which recurred during the unipolar moment – more specifically their détente from 1991 to 1997, and subsequent rapprochement from 1997 to 2007.

In the first friendly phase, Iran and Saudi Arabia were largely associated with a single great power in a multipolar world, the United Kingdom. Their threat environment and corresponding threat perception limited their rivalry. After their initial contacts were established in the mid-1920s two states (at that time, the Kingdom of Persia and the Kingdom of Hejaz, Najd and its Dependencies) concluded and signed the Friendship Treaty in Tehran in 1929. In the aftermath of the treaty, their diplomatic envoys also accorded reciprocal treatment in accordance with the rules of international law. Historians of Saudi-Iranian relations also documented that the Saudi government and city residents warmly welcomed a naval ship from Persia that docked at Jeddah port.

Throughout this phase, the British regional dominance and common identity of Iran and Saudi Arabia with the British pole reduced the phenomenon of cross-cutting relationships among different axes of conflict that usually exist in the multipolar system. As other great powers played a secondary role in the Persian Gulf, the number of great-great power dyads was reduced, which generally represented a more stable situation for Iran and Saudi Arabia. Any attempt to break this continuity would have resulted in serious trouble. The case of Nazi Germany is illustrative in this regard. Berlin made limited but successful attempts to increase power projection in Iran in the late 1930s and early 1940s. As expected, this gave rise to security tensions, which resulted in the forced abdication of Reza Shah, the swift occupation of Iran by British and Russian troops, and inactive relations with Riyadh.

Throughout this phase, the British regional dominance and common identity of Iran and Saudi Arabia with the British pole reduced the phenomenon of cross-cutting relationships among different axes of conflict that usually exist in the multipolar system. As other great powers played a secondary role in the Persian Gulf, the number of great-great power dyads was reduced, which generally represented a more stable situation for Iran and Saudi Arabia. Any attempt to break this continuity would have resulted in serious trouble. The case of Nazi Germany is illustrative in this regard. Berlin made limited but successful attempts to increase power projection in Iran in the late 1930s and early 1940s. As expected, this gave rise to security tensions, which resulted in the forced abdication of Reza Shah, the swift occupation of Iran by British and Russian troops, and inactive relations with Riyadh.

In the second friendly phase, Iran and Saudi Arabia shared their alliance with a common great power in a bipolar system, the United States, and the tightness of the system made it difficult for them to oppose each other. The in-depth historical account of their diplomatic relations since the 1950s points to a systemic recurrence of friendlier behavior for three subsequent decades. The strength of their collaboration in 1950s was expressed in different arenas, such as converging Saudi-Iranian interests in Egypt after Gamal Abdel Nasser overthrew King Farouk in the socialist-republican coup; joint support for Jordan when revolts threatened the continuity of the Hashemite monarchy; and preventing a socialist coup in Lebanon.

In the 1960s, Iran supported Saudi Arabia in a proxy war against Egypt in Northern Yemen. Two friendly states also signed the Agreement over the Islands of al-‘Arabiya and Farsi, while in the 1970s, Iran and Saudi Arabia were twin pillars of the US axis and were the closest of allies. That relationship was so close that Iran declared a week of mourning when King Faisal was assassinated in 1975.The dominant structural force that prevailed through the three decades or so of close bilateral ties is the bipolar world order of the time, and the fact that both sides allied themselves with the United States. It also explains why Iran and Saudi Arabia feared other revolutionary states that identified themselves with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

This fear was great enough that it not only drew Saudi Arabia, a Wahhabi Islamist state, and Iran, then a nationalist and pro-secular Shia state, together, but also made them more receptive to Islamic political movements, such as the Muslim Brotherhood. Tehran’s departure from the US-led pole in 1979. generated an enormous amount of pressure on both states to significantly alter their behavior. Iran abandoned friendly connections with Saudi Arabia, which maintained an active and strategic relationship with the US, while the Saudis limited friendly connections with Iran because of its messianic refusal to abide by the existing order. New structural realities led to the creation of the Gulf Cooperation Council in January 1981 and Iraq-Iran War in the 1980s.

Shared threat perception from American unipolarity

In the third friendly phase, a sole superpower in a unipolar world was not restrained from the Middle East and Persian Gulf region in the 1990s and early 2000s. Spreading democracy abroad was a high-priority goal for two successive US administrations since the end of the Cold War. In his 1992 campaign Bill Clinton frequently insisted that the promotion of democracy would be a top priority of his foreign policy. His assistant for national security defined the central theme of Clinton foreign policy as the “enlargement of democracy”. President George W. Bush used military might to try to turn Afghanistan and Iraq to begin with, and later even other states across the Middle East into liberal democracies. He said: “By the resolve and purpose of America, and of our friends and allies, we will make this an age of progress and liberty. Free people will set the course of history, and free people will keep the peace of the world.”

In the third friendly phase, a sole superpower in a unipolar world was not restrained from the Middle East and Persian Gulf region in the 1990s and early 2000s. Spreading democracy abroad was a high-priority goal for two successive US administrations since the end of the Cold War. In his 1992 campaign Bill Clinton frequently insisted that the promotion of democracy would be a top priority of his foreign policy. His assistant for national security defined the central theme of Clinton foreign policy as the “enlargement of democracy”. President George W. Bush used military might to try to turn Afghanistan and Iraq to begin with, and later even other states across the Middle East into liberal democracies. He said: “By the resolve and purpose of America, and of our friends and allies, we will make this an age of progress and liberty. Free people will set the course of history, and free people will keep the peace of the world.”

However, political elites in Iran and Saudi Arabia generally disliked what John Mearsheimer calls “a liberal unipole” in which the United States pursues a policy of “liberal hegemony” – making Muslim-majority states in the image of liberal elites in the US. Indeed, there is a problem in Iran and Saudi Arabia with accepting the universality and superiority of liberal ideology that is pursued by the political liberal elite in the West. Additional systemic reason for their relatively constructive relations during this period was unrivaled US hegemony. Iran and Saudi Arabia were fearful and resistant to this pressure from the US in different ways. Not surprisingly, they have pursued a policy of détente from 1991 to 1997 and closer diplomatic ties from late 1990s to mid-2000s.

It is not difficult to find historical validation for this argument. Riyadh and Tehran were exceptionally close between 1997 and 2001. This was the most constructive period of Saudi-Iranian rapprochement, during which the Cooperation Agreement and Security Accord were concluded in 1998 and 2001, respectively. At the peak of their collaboration in 2000, the Iranian Minister of Defense, Admiral Ali Shamkhani, proposed new arrangements for collective security in the Persian Gulf that excluded the United States, including the creation of a joint army “for the defense of the Muslim world”. “The sky’s the limit for Iranian–Saudi Arabian relations and co-operation, as the whole of Islamic Iran’s military might is in the service of our Saudi and Muslim brothers,” he said.

Unsurprisingly, the Saudis balked. They were not ready to sacrifice a long-term security arrangement with the US. Doing so would be akin to Japan entering into a security pact with China while exiting its defense treaty with the US. This also explains why Saudi Arabia signed an agreement with Iran on internal security matters in 2001 that excluded military collaboration. The massive American military presence in the region essentially acted as a stabilizer for Saudi–Iran ties. That it took a scant three weeks for the US to pummel the Iraqi army and overthrow Saddam Hussein’s regime did not go unnoticed in Tehran.

With one side cowed and the other reassured by American military might, Iran and Saudi Arabia pursued cautious policies and preserved dialogue at a high-level. Ali Larijani alone paid four official visits to Saudi Arabia for consultations with Prince Bandar and King Abdullah. President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was accorded red carpet treatment and was greeted by the Saudi King at the airport when he arrived in Riyadh in March 2007. The Saudi press hailed Ahmadinejad’s visit as another sign of deepening ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and referred to the two countries as “brotherly nations.”

However, Saudi Arabia was getting more fearful from the new American posture in the Middle East than from its promotion of liberal democracy. With a pending American exit from Iraq by 2011., Tehran was assured of having more space to expand its influence and growing proxy network. Iraq was no longer an occupied, neutral or buffer state between Riyadh and Tehran. Instead, it tilted towards Iran on all major regional issues. Iraqi Shia militia groups also grew bolder, and were free to carry out mortar attacks across the border with Saudi Arabia.

Hence, the exit of Saudi Arabia’s security blanket left them worried about American commitment to maintaining the regional order. That worry amplified when President Barack Obama announced a new East Asia Strategy—also known as the Asia Pivot—in 2012. With this shift, the central role of the US in the Middle East was additionally marginalized. Iran and Saudi Arabia were left to fill the vacuum. While Saudi Arabia felt more vulnerable with the Arab Spring in Bahrain and Yemen, Iranian interests in Syria were under threat. It was a perfect setting for them to return to hostile relations.

Shared preference of pluralization and multipolarity

With changing international order, two regional rivals found themselves in matching mode again in the 2020s. In addition to what they commonly opposed in late 1990s and early 2000s, there is an alternative order for Iran and Saudi Arabia that better fits their international ambitions today. It is about their shared preference for polarization and multipolarity of the international system where their voices can be heard or where they can move from the “periphery” of international politics to the “center”.

With changing international order, two regional rivals found themselves in matching mode again in the 2020s. In addition to what they commonly opposed in late 1990s and early 2000s, there is an alternative order for Iran and Saudi Arabia that better fits their international ambitions today. It is about their shared preference for polarization and multipolarity of the international system where their voices can be heard or where they can move from the “periphery” of international politics to the “center”.

Iran has decided to pursue more independent foreign policy more than four decades ago. Saudi Arabia has chosen a similar path only recently. Although Riyad has long been a US ally, its neutral stance on the crisis in Ukraine, strategic partnership with China, close relations with Russia, exposure to BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, underlines an important shift to new balancing behavior in a new world order where Russia—and China—are equally important.

Moreover, beyond a neutral stance on the war in Ukraine or a closer partnership with Beijing and Moscow, there emerge other assertive foreign policy paradigms with broader regional implications. Among others, Saudi special relations with the US have grown colder. Iran’s long-held official view that collaboration with Saudi Arabia is subject to new arrangements in the Persian Gulf that exclude the US or reduce Saudi dependency on Washington have not changed. This gives Tehran a reason to engage with Riyadh. Given their newly born mutual preference for multipolarity, including their common objection to liberal international order in previous phases, conditions for a Saudi-Iran rapprochement were already set.

Their matching polarity with great power(s) has accurately foreshadowed the friendly course of Iran–Saudi ties over the past 100 years. The nature of this relationship is likely to follow the same pattern in the future as well.

Dr Emir Hadzikadunic is a Senior Research Fellow at the Islamic Renaissance Front. He holds a PhD in International Relations from the International University of Sarajevo and was the Ambassador of Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Islamic Republic of Iran (2010-2013) and Malaysia (2016-2020). He is currently a Distinguished Fellow at Faculty of Administrative Science & Policy Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Malaysia. This essay first appeared at Fair Observer at https://www.fairobserver.com/world-news/saudi-iranian-rapprochements-are-not-new-heres-a-history/

Dr Emir Hadzikadunic is a Senior Research Fellow at the Islamic Renaissance Front. He holds a PhD in International Relations from the International University of Sarajevo and was the Ambassador of Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Islamic Republic of Iran (2010-2013) and Malaysia (2016-2020). He is currently a Distinguished Fellow at Faculty of Administrative Science & Policy Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Malaysia. This essay first appeared at Fair Observer at https://www.fairobserver.com/world-news/saudi-iranian-rapprochements-are-not-new-heres-a-history/