Maung Zarni || 2 April 2022

On March 21, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken announced a (Rohingya) “genocide determination.” The U.S. decision was largely welcomed by Rohingya survivors.

On March 21, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken announced a (Rohingya) “genocide determination.” The U.S. decision was largely welcomed by Rohingya survivors.

Myanmar is a signatory to the interstate treaty Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) or Genocide Convention. Since it launched its first genocidal purge against Rohingyas in February 1978, two successive generations of Rohingya rights activists—some, lawyers—have named the crime their group has endured as genocide and campaigned for international recognition.

As evidenced from numerous “welcoming statements” from refugee camps in Bangladesh and diaspora campaign groups, the Rohingya rightly feel vindicated now that one of the world’s most powerful states has officially called the crimes against them a genocide, albeit after years of strategic avoidance. Within their reasoning for avoidance, was not wanting to rock the country’s Washington-brokered, neo-liberal “democratic transition,” with Aung San Suu Kyi eventually taking the helm as Myanmar state counsellor in 2016.

Washington’s strategic calculation, namely that by not calling crimes against the Rohingya a genocide, the United States would in due course steer Myanmar’s most powerful stakeholder, the military, away from Washington’s number one imperial rival, China, also proved patently false.

Moreover, I would venture a guess that the divestment of the California-headquartered Chevron corporation from its three-decades of highly controversial natural gas production in Myanmar removed a significant corporate barrier in declaring that Myanmar has committed the crime of genocide. The construction of the gas pipeline was associated with the use of forced labor and other crimes against humanity.

Predictably, Myanmar’s coup regime dismissed Blinken’s announcement as “politically motivated.” Likewise, led by Myanmar’s military-patronized Buddhist, Islamic, and Hindu leaders and cronies, the newly formed Interfaith Peace and Harmony Council joined the military regime in dismissing and denouncing Blinken’s “determination” as a fantastical announcement, falsely claiming that there was no corroborating evidence.

The painful truth is that this religious council’s statement and the regime’s dismissal most likely would have been endorsed by Aung San Suu Kyi, had she not been imprisoned after the coup. She was the council’s original patron and the regime’s most significant civilian collaborator.

The painful truth is that this religious council’s statement and the regime’s dismissal most likely would have been endorsed by Aung San Suu Kyi, had she not been imprisoned after the coup. She was the council’s original patron and the regime’s most significant civilian collaborator.

The Burmese Nobel Peace laureate has lost her moral authority and international stature after years of studied silence and evasions over her country’s well-documented genocide. Her old friends and loyal supporters, including the late Desmond Tutu, have publicly called her out on her culpability.

In December 2019, in her capacity as Myanmar state counsellor, the de facto head of state, Suu Kyi traveled to The Hague where she served as the agent or official state representative in The Gambia v. Myanmar case and denied Gambia’s genocide allegations lodged at the UN’s highest court of states, the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Blinken’s “genocide determination” pinned the genocide label exclusively on the country’s military leaders. In fact, genocides are institutional crimes typically planned, organized, managed, executed, and denied by various organs of a state and those who were in charge. During the two genocidal purges of 2016 and 2017, which were the sole focus of the U.S. State Department’s forensic investigation completed in 2018 involving interviews with 1,000 survivors in refugee camps in Bangladesh, Aung San Suu Kyi was Myanmar’s state counsellor, foreign minister, and the autocratic chair of the then ruling National League for Democracy. Her official denial of genocide at the ICJ and her public acts of denial on numerous occasions removed any doubt as to where she stood and what her official and public roles were in the crime which the United States has now officially called a genocide.

On my part, as a Burmese scholar and activist who blew the genocide whistle, I should also share the joy of vindication with my fellow Myanmar people, namely the Rohingya.

In 2014, following a three-year study, I co-authored The Slow-Burning Genocide of Myanmar’s Rohingya, the first academic study of Rohingya persecution using the genocide framework, jointly conducted with my researcher colleague and wife Natalie Brinham (pseudonym Alice Cowley).

But I do not add my voice to the international chorus of welcomes to Blinken’s genocide determination for several reasons.

First, Blinken’s genocide determination was not accompanied by any indication whatsoever that the United States is determined to mobilize its enormous financial, military, and diplomatic clout in the right direction—that is to help the current post-Aung San Suu Kyi wave of popular resistance, armed and non-violent, that seek to delegitimize, weaken, and eventually force the military to relinquish its monopoly over Myanmar’s state institutions, the very institutions and structures which served as the instruments of genocide.

First, Blinken’s genocide determination was not accompanied by any indication whatsoever that the United States is determined to mobilize its enormous financial, military, and diplomatic clout in the right direction—that is to help the current post-Aung San Suu Kyi wave of popular resistance, armed and non-violent, that seek to delegitimize, weaken, and eventually force the military to relinquish its monopoly over Myanmar’s state institutions, the very institutions and structures which served as the instruments of genocide.

Washington is capable of such acts as has been amply demonstrated in its response to Russia’s crimes of aggression against Ukraine. Since February 24, when the Russian tanks rolled across the Ukrainian borders, not a day has gone by, without the United States announcing some kind of concrete punitive measures or threats against Russia.

In my FORSEA Dialogue on Democratic Struggles across Asia on March 21, Ei Thinzar Maung, this year’s Burmese recipient of the U.S. Secretary of State’s International Women of Courage Award, and Padoh Saw Taw Nee, head of the Foreign Affairs Department of the Karen National Union, Myanmar’s oldest resistance organization, publicly urged the United States government to release the $1 billion Myanmar sovereign fund frozen by Blinken’s boss, President Biden, following the coup in Myanmar so that the money could be used to fund Myanmar’s rightful resistance against the “terrorist”-like occupying military.

I am painfully aware that Myanmar people’s armed resistance against the genocidal military is not deemed support-worthy, unlike the Ukrainian resistance that is fighting the West’s proxy war against Putin’s Russia.

I have long shared the widespread dismay towards Washington’s foot-dragging regarding the gravest crimes in international law that has occurred irrespective of the political party in the White House. It’s an entirely different matter when groups such as DAESH, the “Islamic State,” or adversarial state actors (such as China)—then, the U.S. springs into action. After all, these battles advance American strategic agendas.

Using the Genocide Convention only when it serves the U.S. strategic and political interests cheapens the term “genocide” and undermines the gravity of the crimes. The political instrumentalization adds insult to the injuries of many—not only the Rohingyas, but also all other preceding victim groups.

By not calling genocides by their legal name, Washington follows a decades-old pattern of failing to prevent genocide and failing to punish genocidal perpetrators and criminal states. According to Dr. Gregory Stanton, former U.S. diplomat and renowned genocide scholar at Genocide Watch, Bill Clinton’s Secretary of State Warren Christopher was known to have instructed all U.S. missions not to use the word “genocide,” only “acts of genocide” in the midst of Rwanda’s mass killings, while Kofi Annan, under the heavy influence of the Cold War-victorious Americans and in his capacity as head of the UN Peacekeeping Operations at the New York headquarters, ordered the UN Peacekeeping Forces in Kigali, Rwanda to stand down as the genocide was visibly underway.

Samantha Power, Obama’s U.S. representative to the United Nations and now Biden’s head of the United States Agency for International Aid (USAID), won a Pulitzer with her book entitled A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide which indignantly detailed a long history of U.S. failures to do good in cases of genocides. Three successive U.S. presidents, Obama, Trump, and the incumbent Biden, have all been fully aware of the genocidal nature of Myanmar’s persecution of the Rohingya. Painfully, until this week, the United States held its nose.

Samantha Power, Obama’s U.S. representative to the United Nations and now Biden’s head of the United States Agency for International Aid (USAID), won a Pulitzer with her book entitled A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide which indignantly detailed a long history of U.S. failures to do good in cases of genocides. Three successive U.S. presidents, Obama, Trump, and the incumbent Biden, have all been fully aware of the genocidal nature of Myanmar’s persecution of the Rohingya. Painfully, until this week, the United States held its nose.

Rather ironically, Power who, as a former Balkan War journalist, asked, “Why do American leaders who vow ‘never again’ repeatedly fail to stop genocide?” chose to toe Washington’s line when she joined the U.S. government. Wai Wai Nu, a prominent Rohingya campaigner and former trainee in my genocide-sensitivity workshops at the Documentation Centre, Cambodia, recounted to me her meeting with then U.S. representative Madam Power in her office in New York where she was gifted a copy of A Problem from Hell, with an autographic note, which clearly indicated that the best-selling author of U.S. policy failures in genocides KNEW what the Rohingyas were subjected to genocide. Still, Power chose silence.

The historical fact is this: Myanmar’s genocidal purges of the Rohingya Muslims have been on Washington’s radar ever since the late U.S. senator Edward Kennedy, made his visit to Bangladesh in 1978— the year of the first wave of the Rohingya genocidal violence into the then newly independent republic of Bangladesh. Kennedy was instrumental in the U.S. decision to contribute $250,000 to humanitarian relief for “Muslims from Burma” as the victims were then referred to in various regional news outlets such as the Far Eastern Economic Review, Bangkok Post, and Pakistan’s Dawn.

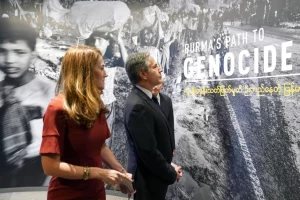

Beyond stating that Washington has made a $1 million contribution to the United Nations’ Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar based in Geneva and Blinken’s “genocide determination” speech, flowery and emotive, at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, no U.S. commitments have been made on specific actions by the Biden administration to support the reversal of the genocidal policies and practices against 600,000 Rohingya trapped inside Myanmar in the Internally displaced persons (IDPs) camps and open-air prisons of Western Myanmar. Nor does Blinken’s act of determination offer any concrete support for Myanmar’s nationwide resistance aimed at dismantling Myanmar’s repressive and murderous structures, also being weaponized against the public at large by the same regime.

Dr Maung Zarni is a UK-based Burmese exile and scholar with thirty over years of experience in international human rights activism. He has co-founded the Free Burma Coalition (1995), the Free Rohingya Coalition (2018), and the Forces of Renewal for Southeast Asia (FORSEA) (2018). This essay also appeared in Politics Today at https://politicstoday.org/united-states-rohingya-genocide-determination/

Dr Maung Zarni is a UK-based Burmese exile and scholar with thirty over years of experience in international human rights activism. He has co-founded the Free Burma Coalition (1995), the Free Rohingya Coalition (2018), and the Forces of Renewal for Southeast Asia (FORSEA) (2018). This essay also appeared in Politics Today at https://politicstoday.org/united-states-rohingya-genocide-determination/